Horned Lark Pencil Sketch p65

Growing up in the southwest corner of New York State, I never came across Horned Larks. For one reason or another they aren’t typically in the area. It’s sad to have missed out on such a great bird! Gazing through field … Continued

Cedar Waxwing Pencil Sketch p64

It’s easy for people who don’t spend much time in nature to overlook something as spectacular as a Cedar Waxwing. They are small, mostly brown birds, and from a distance there isn’t much that grabs your attention. Often it’s their high-pitched, almost … Continued

Male Dimorphic Jumping Spider on Daisy Transparent Watercolor Step-by-step

Most spiders get a bad rap. Almost all are beneficial, devouring garden pests and presenting no harm to humans whatsoever. Sure, some have a sinister look to them, but they mostly live their lives hiding out, waiting for their next meal. In … Continued

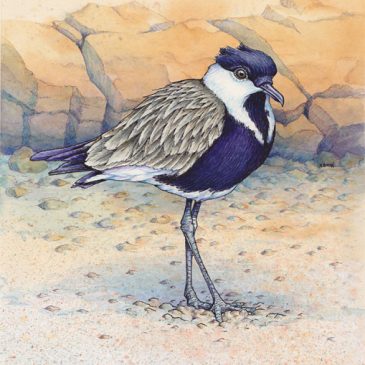

Spur-winged Plover Transparent Watercolor Step-by-step

The boldly patterned Spur-winged Plover (Vanellus spinosus) is a fairly common lapwing from Africa and the Eastern Mediterannean. The bird has a loud call to match it’s in-your-face plumage, described as sounding like “Did he do it?” Of course this just leaves me with more … Continued

American Robin Pencil Sketch p63

American Robins are beautiful birds. They seem to be most commonly seen on a green lawn hunting for worms. I always think it is nice to spot one posing in a tree.

Wattled Jacana Transparent Watercolor Step-by-step

Wattled Jacanas are attractive birds with elongated toes that allow them to stride along water lily pads on the edges of the shallow lakes and ponds where they live in South America. The males incubate a pair of eggs on a floating nest. … Continued

White Rhinoceros Pencil Sketch, p62

I’m officially way behind on posting things. It’s been a busy spring with lots of birding. Here is a drawing of a White Rhinoceros from the Potter Park Zoo here in Lansing. Rhinos are fun to draw. They have a … Continued

Male Dimorphic Jumping Spider Pencil Sketch p61

As you can tell from the content, I intended to post this a few weeks ago, but my spare time was spent birding… Yes! I love spring. I always get excited by the reappearance of plants and animals that didn’t attempt to tough out … Continued

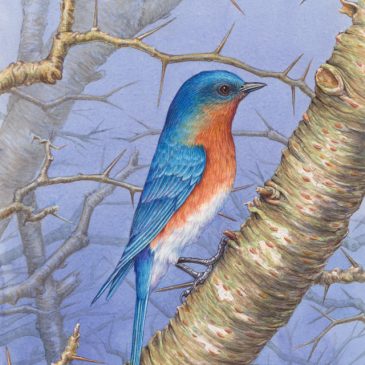

Male Eastern Bluebird on Hawthorn Transparent Watercolor Step-by-step

Over the years we have had Eastern Bluebirds nest in our yard. What an incredible treat! In the past ten years the field nearby has been slowly taken over by trees, and we have seen less and less of them. … Continued

Redbud Treehopper Pencil Sketch p60

I came across numerous examples of these treehoppers feasting on our Redbud tree last summer. They seemed to be more abundant for some reason. My only guess is that the treehoppers liked the fresh, young growth the tree was forced to … Continued